The Saga of Albert K. BRucher

Recently, I was honored with the opportunity to reunite the belongings of a WWII veteran with his son. I have attached my entire “write-up” below, detailing the story (from finding it, to researching the veteran, and to finding his son). I am happy to report that the canteen will be returning home.

- - -

Comprehensive Research "Write-Up" Below, Photos of the Man Himself Below, Canteen Below, Brucher's Diary at Bottom of Page

Canteen that brought us together

The Write-Up

In Memoriam of Brothers Albert K. Brucher (d. 1994) and A. Douglas Brucher (d. 1937)

FOREWARD

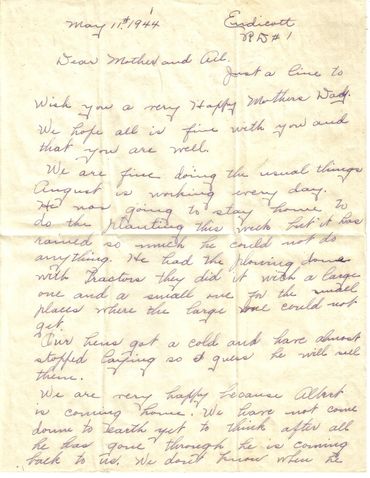

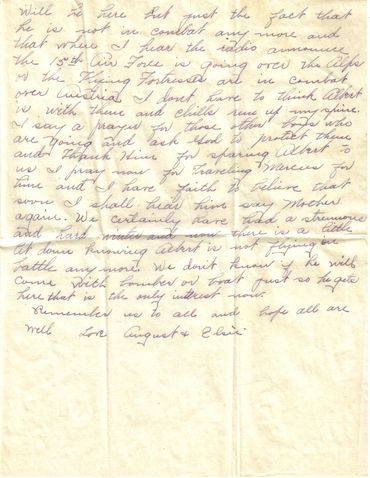

This is a heavily engraved canteen belonging to S/Sgt. Albert K. Brucher of Endicott, New York. I initially bought this canteen out of a basement at face value. For the canteen collectors out there, you will recognize this as a rare M1910 seamless canteen, unmarked but produced prior to the outbreak of WW1. I said to myself, “Hey, this is cool! I’ve already got one of these but I could sell it for 50 or 60 bucks…not a bad price. The gentleman selling it wanted $20. I insisted upon paying $40…he was not a collector. However, when I got home, I pulled it out of the cup, looked at it, set it aside, and forgot about it–nothing too interesting. The cup was snug tight in the cover, so I left it there. A few days passed and I decided to photograph it, as it was sunny outside. Trying to wiggle the cup out of the canvas cover, I felt something; was it a scratch? This aluminum, should be smooth…Blindly feeling it out, I realized that this was deliberate. Excitedly freeing the cup from the clutches of the canvas cover, shivers went down my spine. I ran my fingers across the painstakingly engraved letters, my jaw dropping. “Dad! Come check this out…” My awe was confirmed when my father, not a collector, agreed that it was absolutely remarkable. “I hope you’re not selling that,” he said. No, I would not be selling that. Since it was just a few days before I would be attending my first semester of college, I took those photographs I wanted and continued packing my life into the trunk of the car. I had halted my research for the time being, as I had to get ready for the coming year. However, some months later, I remembered, “Oh yeah…I never really researched that guy…” Sitting in the back of an unimportant lecture, I switched from my class notes to my archive notes. Long story short, with a few excited phone calls in between, it went like this: I began scouring Endicott newspapers, largely coming up dry. Then I had a few breadcrumbs and we got a photo of Albert. I figured that this was amazing–how often do you get to put a face next to this kind of stuff? Then, I found a later article mentioning one Douglas Brucher. I had chills down my spine–I may be able to find this veteran’s son. Immediately searching online, I could not find any reference to Douglas Brucher in New York, nor buried elsewhere. I let out a sigh of relief: He was alive. Taking a guess as to which highschool he may have attended, I started searching through old Endicott highschool yearbooks. I found his photo from the 1960s, but could not find him now. The yearbook noted that Doug was in a highschool band. I looked for him on Facebook, searching his name. No luck. However, I saw a comment on a post, mentioning a 2005 Highschool Reunion. Now this was a 15 year old throwback post, but it gave me hope. Somebody commented about Doug playing in the band. On a whim, I said, let’s see if we can’t find this guy. Finding his bandmates phone number, but not Doug’s, I called and amazingly received an answer. A huge shout out here goes to Eli. For 1) picking up my phone call, 2) not immediately hanging up on me, 3) listening to me talk about the WWII history of an unrelated veteran, and 4) telling me that Doug had moved to another state years ago (which I will refrain from disclosing for privacy reasons). Though Eli had not talked to Doug in years, he was right! Scouring records, I found Doug Brucher’s address listed. Right there next to it was a phone number, so I tried my luck. As the phone stopped ringing, a woman asked who was calling; I asked if this was Doug, knowing that I got the wrong person already…I needed to say something at least! She confirmed the obvious, that no, she was not Doug. I apologized, stating that I must have the wrong number, as this was the one listed online, and explained that I was looking for Doug because I had something that belonged to him and needed to speak with him. I broke into a huge grin as she explained that she was Doug’s wife, and fetched him to the telephone. Next thing I know, I am talking directly to Doug, the son of the veteran whose canteen I had. I asked if he knew anything of his father’s service, to which Doug was keen on why I was curious about his father. Explaining that I had found his dad’s canteen, nearly 3,000 miles away from his current residence, Doug was happy to hear of its existence. He had never seen it nor heard of it, nor had any idea how it found its way into the basement of a suburban Connecticut home. I am happy to say that, after floating around the states (only God knows where else it was) for nearly 80 years, it will finally be returning home to Douglas, who is the rightful heir to his late father’s estate. Doug surprised me once more–in 2014, he had scanned his father’s flight log from the war; he would be emailing me a copy of the log and I would be sending him my research along with photos of his father’s canteen. However, I found that this was not just a flight log. This was a detailed account, with many pictures included, of the entire military career of Albert K. Brucher. With Doug’s permission, I have written it here, so that his father’s bravery and service to his country may not be forgotten. Additionally, a big thanks to Robert Coalter, curator of the Army Air Corps Museum in Texas. With Robert’s help, the story of S/Sgt. Albert Brucher should soon be available publicly, so that generations of young Americans can learn about their patriot forefathers and heroes.

The canteen as-is, though amazing, would not be nearly as historically significant if it were not for the photographs and journal provided by S/Sgt. Brucher’s son. Though I am by no means a poet nor an author, I have tried my best to condense this veteran’s story. However, his own words are far more telling.

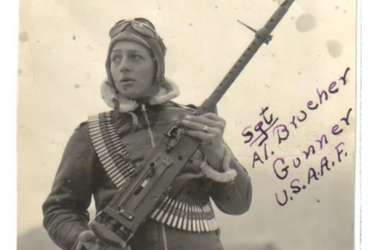

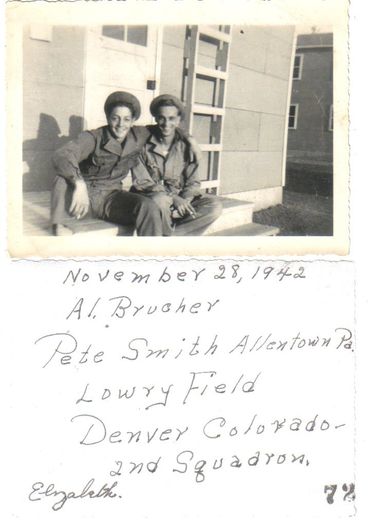

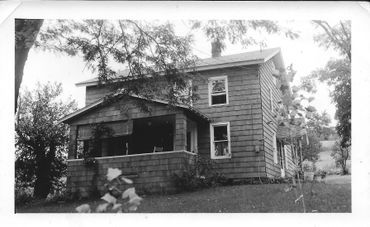

THE STATES

Born June 10th of 1923, Albert Keesling Brucher would have his teenage years violently interrupted by the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Finishing his highschool education, “Al” opted to enlist with the army air corps on September 1st, 1942, leaving his quaint hometown of Endicott, New York. Al was immediately sent to Atlantic City’s army base, before being transferred to the US Army Air Force’s Lowry Field in Colorado for air training. Private Brucher began his airman career studying aircraft armor. He was quickly promoted to sergeant in March of ‘43. Once completing his armorer training at Long Field, in Denver, Brucher went on to Advance Aerial Gunner’s school at Wendover Field, Utah. After receiving his wings, and being promoted to Staff Sergeant in July of ‘43, Brucher was stationed in Tennessee before going overseas for the war. IN-TRANSIT His first location was Belfast, Northern Ireland, where he noted that he met a “very nice young lady” from the newly established Irish Free State. Upon making it to England, S/Sgt. Brucher did not have much to say, except that “the beer they have [in England] is awful.” A day later, Brucher was in Marrakesh, Algeria, before going to “the great city of Casablanka.” He remarked that he wished he could speak French, as his crew would be stuck here for a week or more while they repaired their plane. Landing at Tunis Air Base, Brucher saw his first “real sign of combat,” with shot-down German fighters and wreckage. After a meal of beans and bread, the crew ventured to their home base. The first night, they watched the “Jerries” bomb their supply ships in the Maraysville Harbor. The flack “was thicker than Hell.”

Surrounded by the burnt-out hulks of German tanks, trucks, and aircraft, the men were jealous of the Italians that they took prisoner, noting they they “live like kings’ compared to GIs. Reaching the abandoned Oudna Air Base, men were still dying, as the retreating Germans left booby-traps everywhere, including the mess halls.

ENTERING COMBAT

Brucher’s first mission was a bombing run on the Italian city of Viterbo, August 29, 1943. Proud of their aim, he recounts that they “hit the target on the nose.” He prayed that “lady luck” was with his crew while they dodged accurate flak on the way back to base. However, future missions would be hindered as continually mechanical failures forced the men to turn back. This would become a theme in the future, with numerous consecutive missions ruined by mechanical failures in their B-17 Flying Fortress. In September, Brucher notes how he crippled a Messerschmitt-109, with the other gunners giving them hell. As a tail gunner, Brucher’s mission returns were often eventful. A successful 9-hour mission resulted in 500 pounder bombs dropped on Bologna, Italy. On September 6, 1943, the Luftwaffe dropped Fallschirmjäger paratroopers at Oudna Field No. 2, sabotaging some B-17 airships. However, the next day Brucher and his men were back at it, accurately dropping 300 pounders at 23,000 feet on an Italian airdrome north of Naples. The same night, the Fallschirmjäger returned with “time-bombs and such.” Though roughly 40 men were dropped, 8 were apprehended and the others fled the scene, only blowing up a single B-24 and a single B-17 out of the entire fleet.

After dropping 500 pounders on the German HQ, 10 miles north of Rome, Brucher returns to homebase and rejoices, underlining “Italy Surrendered” in his diary. “One more step ‘twords our victory,” he says. The boys completely destroyed their target, the German HQ of Frascati. More raids and more targets hit for Brucher and his crew. Strategic bridges? Those were a “milk run” for the increasingly experienced crew. Naples bombing? Very good. Rome railroad bridges? Target achieved. German airdrome? Plumes of “black smoke” as they hit a “gasoline dump” with their 100 pounders, dropping 3 dozen of them. However, it was on this day that Brucher saw the first of his comrades die in combat. “All the enlisted men are gone,” he writes of his downed friends.

As mentioned prior, Brucher’s airship would come to be plagued by mechanical failure after mechanical failure. He notes that engines had to be changed, cylinders replaced, superchargers replaced, etc. Furthermore, poor weather continued to inhibit their raids. However, come October, they got back into the thick of it. He remarked that it was “one of the biggest raids ever pulled from [his base].” With heavy flak and reorganized German forces, they began to lose ships at a higher rate, “like when [Brucher] started.” Brucher’s own words cannot be improved upon. The sheer grief that his simple words evoke is unmistakable. “We lost pretty heavy [too]. 5 of my best friends were shot down over Southern Germany. [They] crashed in the mountains. We also lost one other 17 and a B-24. Maybe more. I don’t know yet. No use of writing down the names of the boys. [They’re] all gone now. They sure were a swell bunch of guys. I’m going to miss them.” The simple words of a teenager, thousands of feet in the air, fighting for his country, catching flak and watching loved-ones die, generates an insurmountable pride and sense of patriotism. He is not even given time to grieve, as he must be back in the air without fail, for tomorrow’s mission.

MISSION COMPLETED. TARGET DESTROYED.

“The flak was as thick as hair on a dog,” recalls Brucher. His ship could take half a dozen shots, one right above his head. Fighting “heavy” and “accurate flak,” it is a miracle that they even survived, Brucher only catching a piece of 20mm shrapnel to his hand. Though entitled to a Purple Heart, Brucher acted in his demonstrated nonchalant fashion, opting to tough it out himself. The pace of his journal speeds up here. “Mission [completed]. Target destroyed,” he remarks as he reigns hell upon German bases. Yet again, the inability for a man to grieve properly during these trying times is illustrated. “Received word that Lt. Boregard’s crew was shot down. Wallis, Cuba, Benster, Fales, Hileman, and Zabio are all gone now. Don’t seem possible but it’s true.” Raids ventured further and further into Europe. Weiner, Neustadt. Messerschmitt Factories. However, as they waded further into the Reich, they waded further into treachery. “The Jerries were ready for us.” The Germans were not going down without a fight. Brucher’s outfit “lost heavy,” losing 4 out of 6 ships. The B-24s lost 13 ships. However, these losses were not a one way street, with our favorite tailgunner recounting that “the boys shot down about 30 of them,” when met with numerous FW190 fighters.

Despite false hopes being raised amongst the men, they would still be required to complete 50 missions before going home. Rumors arose that it would be reduced to 30 missions, but that order never came. In November, the men were issued flak suits for their remaining missions, with 28 still required for Brucher. Though they were bulky, heavy, and uncomfortable, the men begrudgingly adorned them to “save [their] hide[s] from getting punched full of holes.”

Future raids included U-Boat docks at Toulon, in occupied France. “The boys,” as we have seen them affectionately referred to as, “[really] did a job” on the German Kriegsmarine forces below. Despite enduring more raids, Brucher had 3 successful missions unaccounted for on his official record. In all of November, according to the books, Brucher was only entitled to 2 successful raids.

Closer and closer into the heart of the Reich, it began taking a toll on the men. “Old John Hanon went crazy” waiting for the Germans to strike in their sleep. Holding steadfast, Brucher remained competent and quick thinking, even in the throes of brutality.

Brucher’s first confirmed kill was on December 20th, 1943, despite having crippled numerous other airships off the record. “It was a regular field day,” he remarks of the mission where he shot his first Messerschmitt-110 (with 3 other men confirming it), “I didn’t ever think I’d get out of it. There was so many of them.” On this mission, they shot down 25 fighters or thereabouts.

A SAD CHRISTMAS

“Bad [weather] today…I seen a mid-air collision of two P-47 Thunderbolts. One cut the tail right off the other. Both [pilots] jumped. One chute didn’t open. [The other opened too] close to the ground. Somebody will have a sad Christmas this year. I just looked up as they went over and didn’t think much about it. Then they hit. Both crashed and burned. About a half a mile from where I was walking.” Brucher could not have been more right. A mere three days before Christmas, this had become a routine occurrence. He did not flinch nor think much about it. This was his life. War does not stop for Christmas. Having been exposed to atrocities for months, it did not phase him in the slightest.

On the 25th of December, Brucher pulled his 25th mission. It was this day that they lost a fearless leader and a good friend. “We lost a great man on that raid. Col. Barley was shot down. No one seen any chutes. Col. Barley was a great man.” While losses continued, there were some silver linings with their new base in Italy. He ate “a second supper at an Italian [family’s] house. Spaghetti,” remarking that he would “long remember that meal.”

Brushes with death became an everyday occurrence. Their trusty B-17, “891,” whose name is still unknown, had some more mechanical failures. After a routine run, their left wheel failed to extend for landing. Luckily, apart from bruises and scratches, the crew was largely unscathed. Though tough as steel, Brucher let his grief through on January 24, 1944. “Date: Jan 24 1944 Place: Italy. Cerignola. The saddest day of my life. This is an entry I had hoped to never make in this book. On the 24th of January, 1944, Lt. Romans, Reinhardt, Camara, and Hinton, Ciotti, Carver, and Sika, went out on a mission and never came back. Fergeson and myself are all that’s left of old crew 20. They were flying 490. Were last seen at two thirty with number one engine [feathered]. [They] dropped down out of formation and went down through the overcast, over enemy territory. That’s the last they were seen. No word has been received as yet. [They] were believed to have ditched the ship off the coast of Yugoslavia.” As the days went on, hope dwindled. “Six days now…everybody has given up hope but Fergeson and I…Still no word of the boys yet…I wonder if I’ll ever make it…Fergeson and I are all that’s left. I still can’t get it through my head that the boys are gone.”

However, almost a full month after their disappearance, word came through. Thanks to underground Yugoslavian resistance, a letter was received, confirming that they were safe. Brucher’s account lines up perfectly with modern archived files. His dear friends, who had successfully ditched their B-17, “The Joker,” were alive and well.

As they reached into late February and into German territory, things were “getting really tough now.” On the 25th of February, they lost 45 of their 100 B-17 ships. Their wing lost 15 ships over Regensberg on one day, losing 30 to 35 on the next.

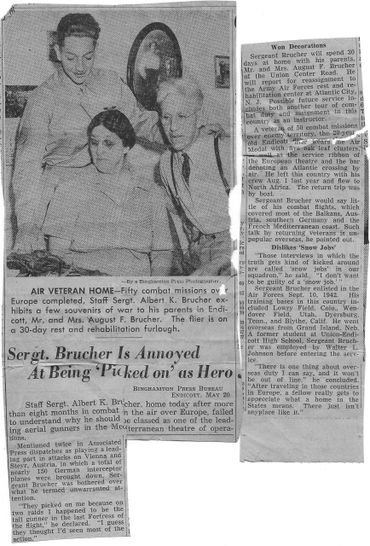

Rightfully notorious for their pension for “souvenirs,” Brucher had to get his own fix. As he was in the sky, and unable to take war-trophies from his targets, he notes in March that he “bought a German dress sword from an English lad,” who had picked it up on a “beach in Messenia.” In the period newspaper articles, which allowed me to connect with the family, a clipping notes of Brucher showing his souvenirs to friends back in Endicott.

As March stretched to April, Brucher’s surprise remainedーsurprise that he was still alive. He expected death and was unafraid, just astonished that he had not met fate yet. “Men shot up or killed every time” was the expectation. “Everybody was drown” and remarking that friends “were all killed when they hit” are unfortunately prevalent in his journal.

In April, Brucher neared completion of his 50 missions. However, a double header, missions number 48 and 49, almost brought that all to an end. Caught by “waves” of Messerschmitt 109s, both the No. 2 and No. 3 engines on Brucher’s ship were shot, knocked out, and caught fire. Diving rapidly, Pilot Lt. McLaufton (likely Lt. McLaughlin) and his expertise saved the men, as the speed of the dive blew the fire out. Dropping over 12,000 feet immediately, P38 fighters “shot the hell out of” the trailing Messerschmitts. On stand-by to bail from the bomber, the order never came. Brucher and his men once again defied the odds. In fact, it was believed that they had not pulled out of the dive, with other men reporting they did not survive the ordeal, “but [they] fooled them!”

50 MISSION CRUSH

April 4, 1944. “The Big Day.” Though promised to return after 50 missions, Brucher was again sent on a double-header. Fergeson, his original crewmate, was hit on this run. However, defying all odds, Brucher racked up a grand total of 51 accounted missions. However, he could not leave without getting revenge for Fergeson; they returned a hellfire to the Germans, shooting down five of them before landing. “With 51 missions, I bring my combat career to a close. Seems funny to say I’m all through” Without a scratch. One small piece of 20-mm in my thumb, not [serious enough] to see the Doc.”

Concluding his journal, Brucher returned to his beloved hometown of Endicott, New York, where he would live until his passing. Albert wanted his sacrifices to be remembered by his family if he died in combat. When he first received the journal in 1942, he scrawled his address, life insurance amount, and the following: “In case of my earth, please see that this book reaches above [address].” Luckily, his story does not have to be remembered under those pretenses. Surviving the ordeal, he will be remembered not just as a combat-tested American hero, but as a boy; Albert K. Brucher was nothing but a boy who sacrificed his youth, his innocence, and gave his all for his country, in pursuit of what is right and just. It was not due to politicians nor negotiations that this war was won, but boys like Al, who answered the call to arms when the free world was threatened. It was not grown men nor extraordinary superhumans, but simply boys with extraordinary willpower, grit, perseverance, and guts. These boys were robbed of their innocence, forced to become men, and give their all. It was these boys who earned the right to be called the Greatest Generation.

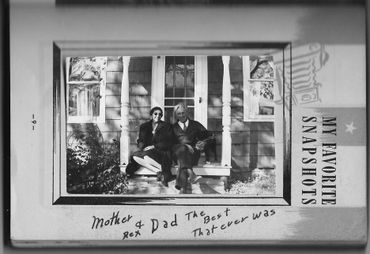

CIVILIAN LIFE

Shortly after his return to the US, Brucher was engaged and married to Miss Pearl M. Lipka, in Buffalo, New York. They returned to Endicott, where they happily lived out the rest of their days. Albert lived to be 70 years old, passing in 1994. His wife Pearl lived until 2009, being reunited with her husband. She never remarried. The two are now at peace together, buried in New York.

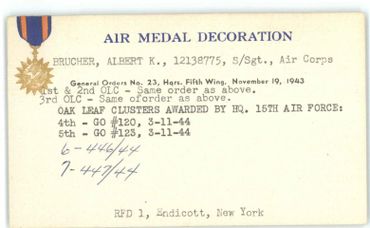

Albert joined his local VFW after the war, spending time with his comrades and friends. Brucher had just purchased his own car after returning. However, it caught fire and was damaged significantly. After this, Brucher opted to serve the community even further, studying and passing the Fireman Exam, keeping Endicott safe for years to come. Even after returning, Brucher was issued medals for his time in combat. He ended with a whopping 7 Oak Leaf Clusters on the Air Medal he was awarded. By some stroke of luck, a completely negligible dinner party, with no real significance whatsoever, was reported in the paper. It noted that Mr. and Mrs. Albert Brucher were attending said dinner–with their young son, Douglas. This is what made the entire reunion (being Douglas with his father’s canteen) possible. So, to whoever it may be out there that decided to publish this insignificant sentence, in a further insignificant article, dead or alive, I owe you a huge thank you; this is the person that made it possible.

Newspaper clippings

Copyright © 2022 Northeast Militaria - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.